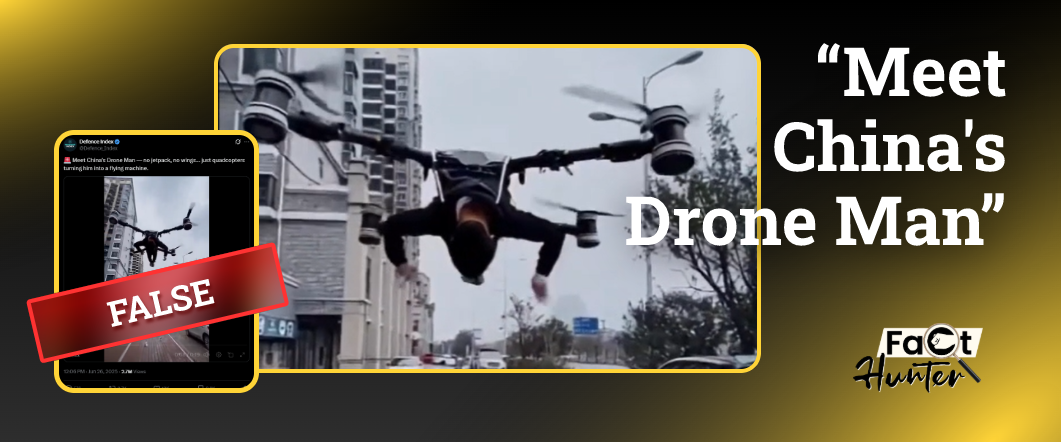

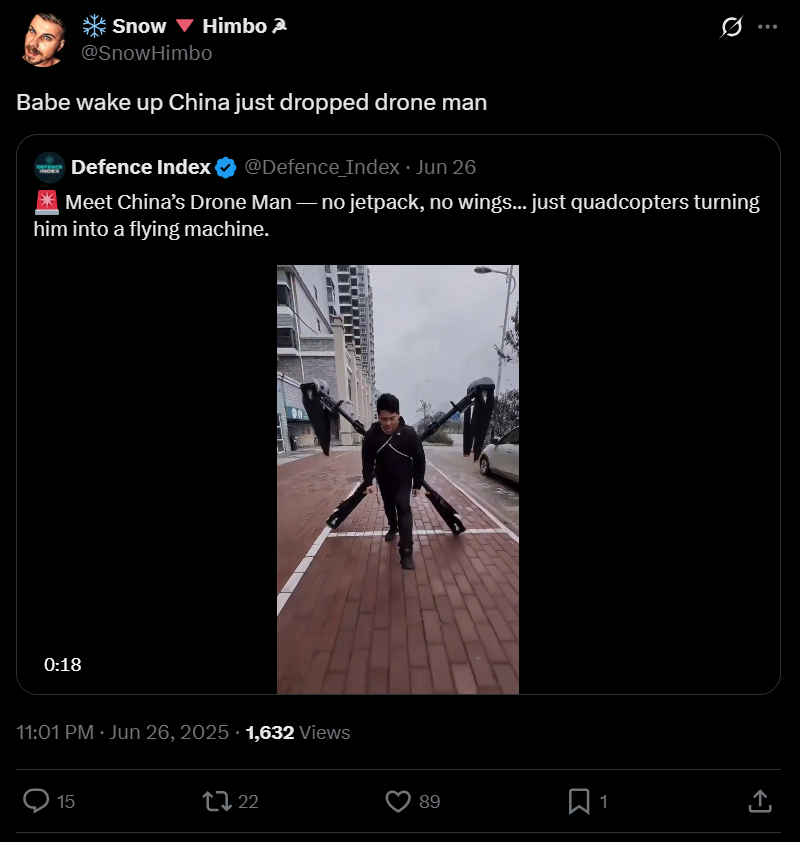

1. “Meet China’s Drone Man”

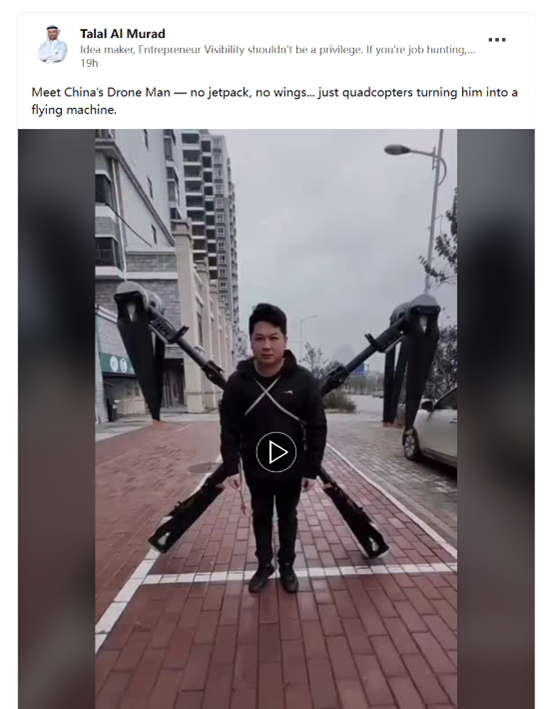

On June 26, 2025, a video was posted by a military influencer on X, captioned “Meet China’s Drone Man.” This video shows a Chinese man flying with a drone. However, while the man and device are real, the takeoff was digitally fabricated. It was subsequently reposted in multiple languages, spreading misleadingly across platforms like YouTube and LinkedIn.

To understand how such deceptive content spreads, we investigate the journey of this particular video from its origin to its global amplification.

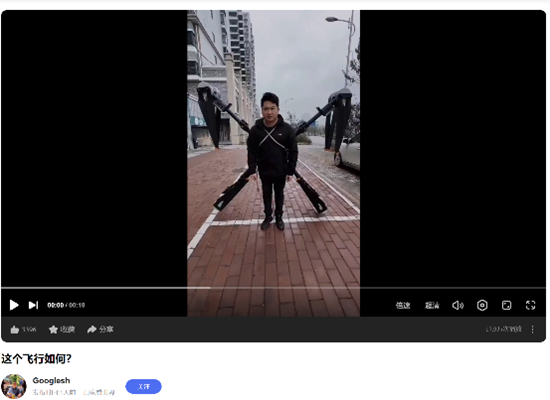

On February 21, 2025, a Chinese user on Douyin posted a humorous video featuring a man strapped to a DJI T100 drone. The clip, clearly staged for entertainment, did not show the drone actually lifting off.

However, on June 26, a manipulated version depicting the man taking off began circulating on Chinese social media. This altered footage was digitally fabricated for comedic effect and virality, inadvertently contributing to disinformation.

Later that same day, the same doctored clip appeared on global platforms such as X, reposted by influencers like Defence Index. With a uniform caption – “Meet China’s Drone Man” – and translated into multiple languages, the video was reframed as a showcase of China’s military-technology capabilities, leading to the spread of misinformation on a global scale.

2. The ripple effect: how disinformation contaminates our shared reality

2.1 How users reacted to the video

User responses to the AI-generated “Drone Man” video on social media can be broadly categorized into three types:

- Debunking and identification as AI

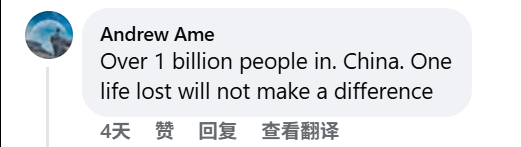

A portion of users recognized the video as artificially generated or manipulated, pointing out telltale visual inconsistencies and labeling it as synthetic content. - Mockery and criticism of China’s drone practices

Users have mocked China’s drone practices as careless and absurd. They have highlighted the lack of safety measures and treated the video as proof of China’s disregard for human life – “no helmet, no protection” – even joking that “one life lost will not make a difference.”

Many have dismissed the footage as staged or propagandistic, calling it “Chinese propaganda nonsense.”

- Narratives of technological threat

A more concerning pattern emerged in comments linking the video to broader geopolitical narratives, particularly the idea of a looming “technological arms race.” Many users interpret the video as a sign of China’s accelerating technological capabilities, often projecting it onto imagined future scenarios. Comments like “This is how the first mosquito with a gun gonna look in 2042” or “Babe wake up, China just dropped drone man” reflect a mix of humor and unease about potential militarized applications.

Others view it through a geopolitical lens, highlighting tech competition. Comments like“Why can’t India compete with China in technology?” and “Japan… lost again…” suggest comparative anxieties.

While a small number of users detected and pointed out the video’s AI manipulation, a significant portion of the audience expressed belief and offered commentary.

2.2 False information as environmental contamination

Most alarming was the sentiment expressed by some users who, despite acknowledging the video might be fake, still commented something along the lines of “I want to believe.” This reveals a shift in how information is consumed: emotional gratification often takes precedence over verified truth. People increasingly share and engage with what they want to be true, not what has been proven to be true.

Such disinformation acts like environmental pollution in our media ecosystem – persisting, embedding in public consciousness and subtly altering collective perceptions over time. Stephan Lewandowsky and colleagues (2012) documented the “continued influence effect,” showing that misinformation often continues to affect memory and reasoning even after it’s been debunked[1]. Gordon Pennycook and David Rand (2021) further demonstrated that repeated exposure to unverified content weakens people’s critical thinking, making them more prone to accept falsehoods [2]. Synthetic media exploits this vulnerability. Like a virus, it evolves emotionally, repeatedly circulating and shaping narratives about national identity or technological supremacy – not to enlighten, but to resonate emotionally and mold belief systems.

3. AI’s Truth Deception: When Seeing No Longer Means Believing

According to Truth-Default Theory [3], we generally assume messages are true unless given strong reason to doubt them, especially when context is ambiguous. Information Manipulation Theory [4] adds that deceptive cues – omitted facts, vague framing – make it easier to mislead audiences. AI exploits these cognitive shortcuts, producing visuals and text that feel authentic yet obscure the truth. As AI-generated content becomes ever more lifelike and emotionally compelling, the human default to trust what we see is being weaponized. Consequently, the distinction between misinformation (unintentional falsehoods) and disinformation (intentional deception) is fading.

Given this blurred reality, mere fact-checking is no longer sufficient. Instead, we must cultivate strong media literacy. In a world where AI can convincingly fabricate almost anything, developing a habit of questioning, verifying and understanding AI’s methods isn’t optional – it’s essential.

Reference

[1] Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612451018

[2] Pennycook, G., Epstein, Z., Mosleh, M., Arechar, A. A., Eckles, D., & Rand, D. G. (2021). Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature, 592(7855), 590–595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03344-2

[3] Levine, T. R. (2014). Truth-Default Theory (TDT): A Theory of Human Deception and Deception Detection. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 33(4), 378–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X14535916

[4] McCornack, S. A. (1992). Information manipulation theory. Communication Monographs, 59(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759209376245